Searching for the real Edwin Díaz

Edwin Díaz fired 483 pitches in 2020, and most of them twisted, turned and ducked away from bats until they hit the catcher’s mitt with a thud. But the one pitch Mets fans probably remember most was a crushing (literally and figuratively) home run he gave up to Marcell Ozuna in July. Ironically, it was on a pitch that tells part of the story of how the young closer was able to regain his form.

Since entering the league in 2016, Diaz has only given up two home runs to right-handed hitters on pitches located on the outer third of the plate: the one to Ozuna and another in 2019 to Kurt Suzuki that wasn’t quite as close to the strike zone’s edge. In contrast, righties have turned ten pitches on the inner third of the dish into long balls, while slugging .639 against those offerings (compared to .291 on outside strikes).

This explains why Díaz located his fastballs the way he did vs right-handed hitters last season, as you can see the contrast between 2020 and 2019 in the graphic below.

If Díaz keeps the ball in the ballpark during his 2019 debut campaign in Queens, the Mets probably make the playoffs. And who knows what would have happened after that. But he didn’t. And part of the reason was because he didn’t throw enough fastballs like he did to Ozuna last July.

Mets Fix is a newsletter that publishes every weekday morning at 8:00am with all the latest Mets news, links, and analysis (like this). Sign-up for FREE below:

If only it was that simple. Diaz burst onto the scene in Seattle as a flamethrower with a delivery that caught the air like a jazz note. It was unpredictable, had sharp edges, and exploded at the right times. While the beauty of jazz is that it lacks form, as a pitcher, even the sweetest delivery is strictly mechanical.

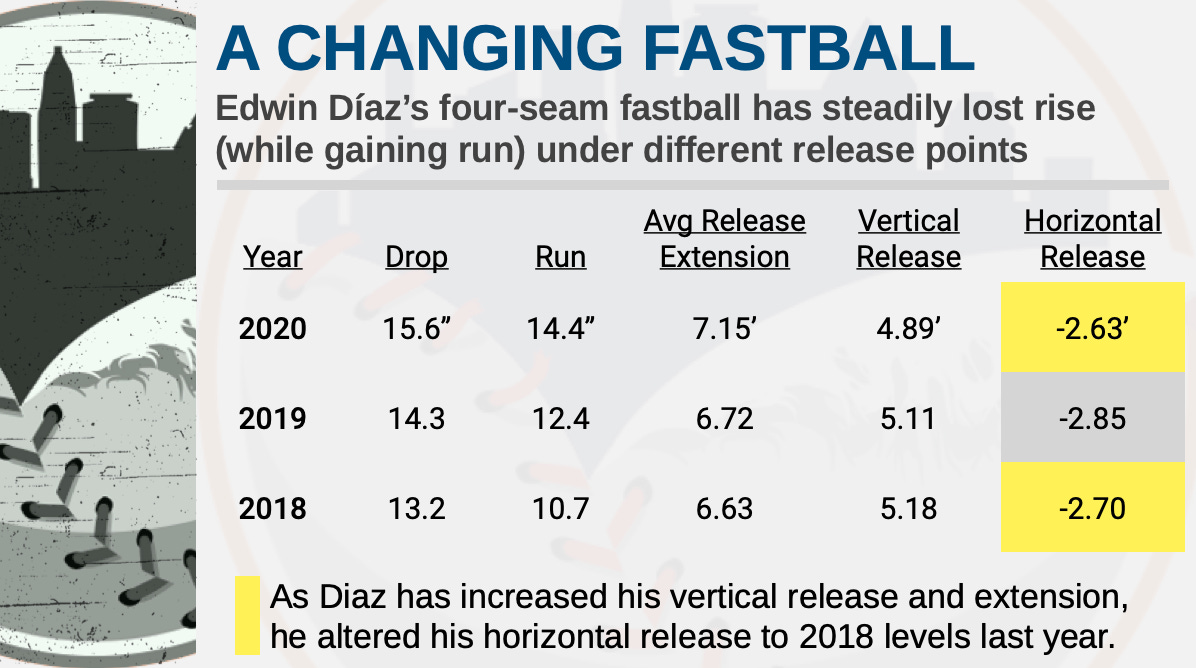

For Edwin Diaz to continue as an elite closer, he needs to prove that his choppy mechanics and uneven command have settled into a rhythm. Since becoming an All-Star in 2018 and being traded to New York, he has tweaked almost every aspect of his release point, including his extension (how far he extends his arm before delivering the pitch). This has resulted in drastic changes in movement, command, and results.

Which brings us to his slider—a pitch that has evolved over his career from one with a strong bite that generated chase rates in the 45 percent range to one with less depth but still capable of producing elite swinging strike results.

Thanks to some advice from Jacob deGrom, Diaz changed the grip on his slider late in the 2019 season and the results carried over into 2020. Instead of trying to steal extra strikes with his slider up in the zone, he went back to earning them by getting hitters to chase it down near the dirt. Seven of the home runs he gave up during his first season with the Mets amazingly came with 2 strikes, and four of those on 0-2 or 1-2 counts. Part of this was because his slider was less efficient as a put-away pitch due to poor command. He improved that last season and his slider’s Put Away % ranked near the top of the league.

The key is making the pitch work off his fastball, which he was able to do in the pandemic-shortened season, despite having two very distinct release points that suggested he could have been tipping his pitches (more on this another day).

When you are Edwin Diaz and you throw 98 MPH cheese with a slider that crumbles like feta, the difference in the release points between pitch types matters less than the path each pitch follows when it leaves the hand. By adjusting the release point on his fastball (which consequently created a greater release point gap compared to his slider), he found better results last year, as he explained earlier this week.

“I think the biggest difference was the location of my pitches, being able to command my fastball and my slider,” Diaz said [via the NY Post], attributing his improved command to slight mechanical tweaks he made after watching video.

We can see the mechanical changes he has been making to his fastball delivery in the table below.

Over the past three seasons, his fastball has added more drop (less rise) and greater run, while his average release extension and vertical release point have followed a straight slope. Where there’s a break in the pattern is his horizontal release point. As highlighted in yellow, he shortened his release in 2020 to more closely resemble his approach during his last season with the Mariners. This could be the tweak he alluded to in his press conference earlier this week.

Building off research in 2019 from Chris Russo (no, not the Mad Dog) on FanGraphs, I looked at how Diaz performed on pitches he delivered with “extreme” horizontal extension (greater than 2.85 inches) vs “normal” extension (less than 2.85 inches), and found the results to be quite telling. If you’re not familiar with xwOBA, just think of it as a number that tells us how much damage opposing hitters should have done off these pitches. It’s clear that Díaz performs better when he doesn’t extend his arm too far horizontally to release the baseball. He essentially rid himself of long extensions in 2020.

Diaz throws his 4-seam with 97% spin efficiency, meaning there would be very little side-to-side movement if he threw it directly over the top. But by delivering it from a slight angle (1:45 on a clock), he adds arm-side movement at the expense of vertical rise.

This means when Diaz is trying to pitch away to right-handed hitters, he runs the risk of his fastball tailing back over the plate. You can just cock back and throw a 98 MPH pitch with rise and an evil cousin that breaks in the opposite direction, but without that rise or steady command, even a fast pitch becomes hittable.

That said, it’s hard to ignore the results Diaz put up last season with his fastball. Pitchers search for rise to induce swings and misses, something he was able to accomplish at a career-best rate with less vertical movement. Instead of getting whiffs up in the zone (as any reasonable person with a 98 MPH fastball would try to do in today’s game), he peppered the outside edge of the plate against right-handers (as discussed earlier).

For the Mets’ coaching staff, they need to balance the comfort level Diaz has pitching from his current release points, which seemingly translate into better command, with the temptation to tweak his fastball design to facilitate better stuff.

Early in the season, it will be interesting to watch if Diaz follows these trends that made him successful in 2020:

Maintain consistency with his mechanics.

Continue to locate fastballs on the outer third of the strike zone.

Increased slider usage with put-away command.

If he does, the Mets could have themselves a better bullpen than fans might think.